Only a few individuals were interested in Polish–German reconciliation in the first twenty years after World War II. These pioneers were mainly representatives of churches and religious organisations. As early as the 1940s, the Polish Primate called on Poles to forgive the Germans, but it took almost 15 years for the first more serious reconciliation initiatives. In 1958, at the Synod of the Evangelical Church in Germany, Aktion Sühnezeichen Friedensdienste (Action Reconciliation Service for Peace) was established, one of the main goals of which was Polish–German reconciliation. In 1960, on the occasion of the feast of St Jadwiga, revered in both Poland and Germany, the then Archbishop of Berlin, Julius Döpfner, called on the Germans to assume responsibility for World War II. At the same time, Fr Kurt Reuter from a parish near Berlin was corresponding with almost all bishops and seminaries in Poland, organising religious literature and liturgical books unavailable in Poland to be sent to them. In 1964, representatives of Pax Christi, and in 1965, Aktion Sühnezeichen, organised penitential pilgrimages to Poland. The Evangelical Church in Germany published in 1961 (1962) the Tübingen Memorandum, and in 1965 the so-called Eastern Memorandum, in which the German government was called upon to recognise the border on the Oder and Neisse. In Poland, activities aimed at reconciliation with Germany were organised by Archbishop Bolesław Kominek from Wrocław. He wrote many texts on this subject, maintained contacts with German bishops and Christian activists, especially from the Pax Christi and Aktion Sühnezeichen circles, interested in improving relations with Poland. These included Günter Särchen, Alfins Erb, Walter Dirks and Hansjakob Stehle. Catholic activists associated with Tygodnik Powszechny also played an important role.

“We want good relations with our neighbours based on trust. We have forgiven much, very much. And today we forgive everything once again. We renounce hatred. We are not looking for revenge. We want to be an active factor in the international order, rapprochement and cooperation for all humanity.”

The letter which changed Europe

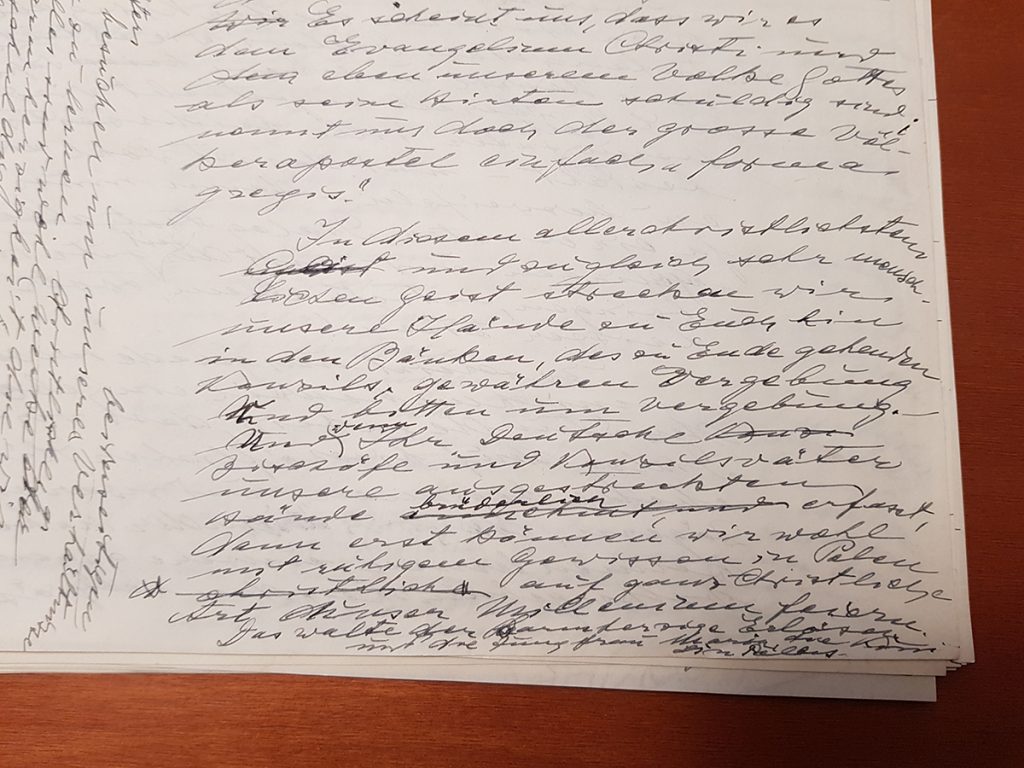

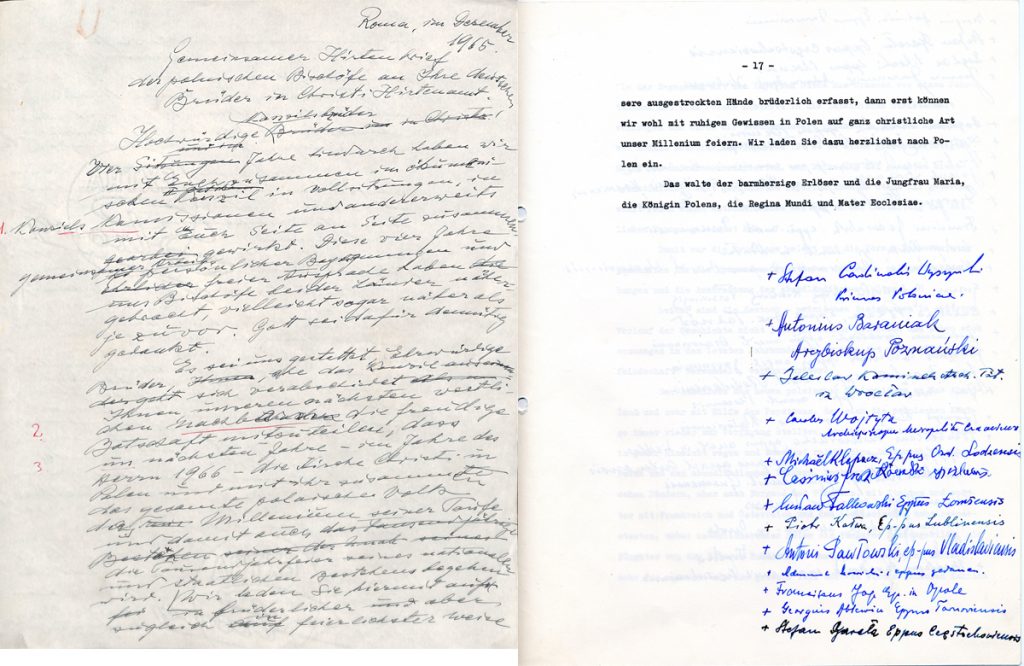

The Letter from the Polish bishops, originally entitled “Botschaft der polnischen Bischöfe an Ihre deutschen Brüder in Christi Hirtenamt” (The message of Polish bishops to their German brothers in Christ’s pastoral office), is a letter sent by the Polish bishops to the German bishops on 18 November 1965 during the last session of the Second Vatican Council. This document was an invitation for Germans to take part in the celebrations of the 1000th anniversary of Christianity in Poland, which was to occur in 1966. The invitation was originally a message that was to lay the foundations for Polish–German reconciliation and overcome hostility between the two nations resulting from the Second World War.

The Letter contains a description summarising Polish–German relations over the course of a thousand years. However, contrary to the thesis of “eternal hostility” between the two nations promoted by the communist authorities, the narrative indicated that in these accounts, apart from difficult, negative moments, there were many periods of fruitful cooperation for both parties. The text also emphasised that, through mutual interactions, Poland and Germany had contributed to the development of European civilisation. In the Letter, for the first time in Poland, the German anti-Nazi opposition was mentioned, the suffering of the displaced Germans, and the German bishops were asked to thank the Protestants in Germany for their involvement in building an agreement with Poland. This was a reference to the Eastern Memorandum of the German Evangelical Church of 1 October 1965. The bishops also mentioned the topic of the Polish–German border, emphasising that it was the main problem in relations at the time. The message of the Letter is based on the assumption that a significant element of European culture is Christian culture and includes a program of Polish–German reconciliation based on truth, as well as readiness for reconciliation and mutual forgiveness.

“In this most Christian, but also very human spirit, we extend our hands to you, sitting here on the benches of the concluding Council, and we forgive and ask for forgiveness. And if you, the German bishops and Council Fathers, take our outstretched hands fraternally, then and only then will we be able to celebrate our Millennium with a clear conscience in the most Christian way”.