The invitation was intended as a message that would lay the foundations for Polish-German reconciliation and overcoming the hostility between the two nations that resulted from World War II. German atrocities on Polish territories in 1939-1945 strengthened the image of Germans as enemies who hated Poles. The aversion to Germans after 1945 was so great in Poland that the word “German” was written with a lowercase letter to show disrespect, and it was impossible to find anyone who had not experienced some kind of harm or personal loss during the war caused by the Germans. On the other hand, in Germany the Poles were perceived as responsible for taking away the territories east of the Oder and Lusatian Neisse (border changes) and for the resettlement of the German population. It was not seen in Germany that the decisions were made by the great powers (USSR, USA, and Great Britain).

At the same time, historical narratives in Poland argued, with the support of the propaganda messages of the communist authorities, that this enmity was “eternal,” that Poles and Germans had always stood on opposite sides, and that they were doomed to this enmity in the future. In this situation the Polish bishops understood that it was their duty to change such a short-sighted way of thinking. They believed that this would only be possible if the relations with Germany was based on Christian values.

The problem of tense Polish-German relations, including the final settlement of the Polish-German border on the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, was one of the key international security issues in Europe after World War II, and thus influenced the process of European integration. It can be even argued that without correct regulation of Polish-German relations, the creation of the European Union in its current shape would be impossible. The process of reconciliation paved the way to political decisions and changed the mutual perceptions (change of stereotypes), caused mutual respect, acceptance of the status quo regarding the border, and finally the establishment of multifaceted cooperation between the two nations.

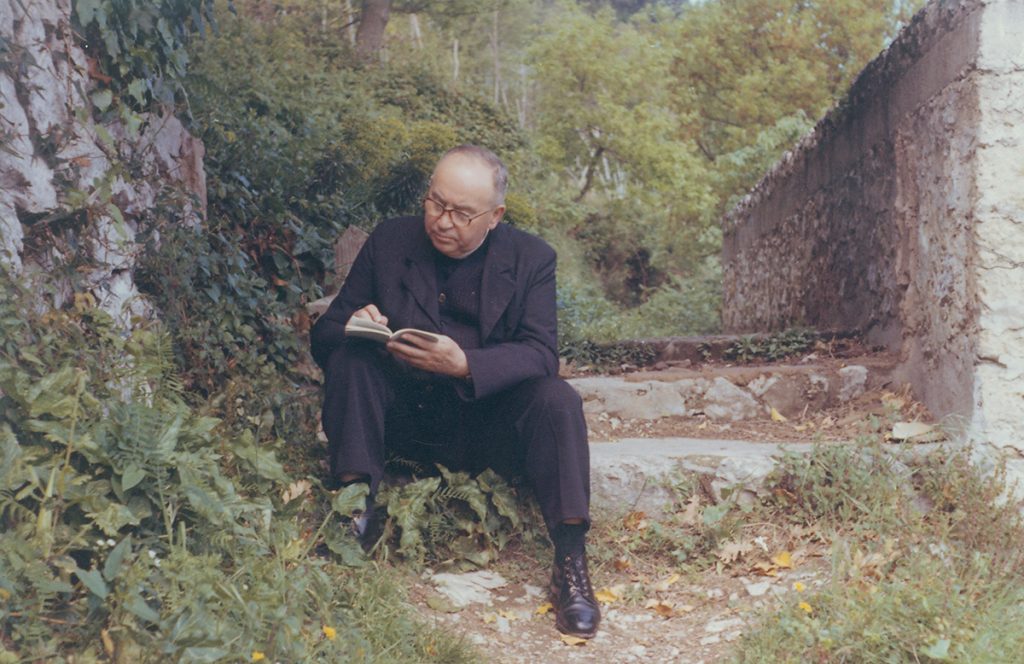

The preparation of the letter to the German bishops was entrusted to the archbishop of Wrocław — Bolesław Kominek.

Meeting between Cardinal Bolesław Kominek and Polish bishops, and members of the Bensberg Circle. From left to right: Karlheinz Koppe, Mechtild Fischer, Cardinal Bolesław Kominek, Elmar Maria Lorey, Rev. Prof. Norbert Greinacher, Manfred Seidler, unknown person; Photo: Winfried Lipscher, “Remembrance and Future” Centre.

Archbishop Bolesław Kominek was the most well-prepared person for this task due to the actions he had undertaken to improve Polish-German relations. He had written many texts on this subject, corresponded with many opinion-forming people, met with German bishops and activists, especially from the Pax Christi and Aktion Sühnezeichen circles, interested in improving relations with Poland (including Günter Särchen, Fr Kurt Reuter, Hansjakob Stehle). It should be noted that the author of the Letter in his earlier texts from the 1960s, in addition to defending Polish rights to the Western and Northern Territories, had called for dialogue and respect for German cultural heritage. In one of his programmatic texts from 1964, he wrote about dialogue as an instrument for carrying out the apostolic mission. Without indicating that it was the Germans, although it seems that it was the western neighbour he meant, he wrote: “The spectre of hatred and hostility fade here. […] We sense and notice in many places the gesture of outstretched hands, we notice the first steps to dialogue. And we, we too, are becoming more open.” In the texts and speeches of Bolesław Kominek that preceded the Letter, one can find certain phrases that were later included in the Letter itself, including the most famous phrase “we forgive and ask for forgiveness,” which he used in the summer of 1965 in his speech at Góra Świętej Anny, on the occasion of the celebration of the 20th anniversary of Polish church administration in the Western Territories, when he was describing the relationship between the immigrant population and the indigenous people in Silesian Opole.

It should be noted that in the mid-1960s, the relations between Polish bishops and German bishops were one of the most difficult ones due to the unregularised status of the Church in western Poland, which had belonged to Germany before World War II. The situation was complicated by the use of historical arguments by Polish hierarchs in favour of the Polish presence in these areas, and by referring to the so-called Piast past (i.e. to medieval times, when these lands belonged to Polish princes), which closely resembled the expressions used by communist propaganda. At the same time, it should be noted that on the German side for many years after the war, even Catholics did not perceive the need to assume responsibility for World War II and reconcile with Poland. The first ideas of changes were born in Christian circles, mainly Protestant. Nevertheless, the Germans, who after 1945 were forced to leave Lower Silesia, Pomerania and Warmia-Masuria, waited for the possibility for the German state to regain these regions in the 1960s. For this reason, all conciliatory gestures with Poland related to the acceptance of the post-war border changes were met with violent protests by the displaced Germans. This was the case after the famous sermon from 1960 by the then Berlin bishop Julius Döpfner, who on the occasion of the feast of St Hedwig of Silesia, spoke about the responsibility of the Germans for the Second World War: “Woe to the Germans who do not want to see the causes of this tragedy and forget to repent for the harm done.” He also mentioned the tragedy of resettlement, although he also saw the need for reconciliation: “Shouldn’t we, through St Hedwig, shake hands? Is the unanimous existence of both nations not more important to the future than the problem of borders?”

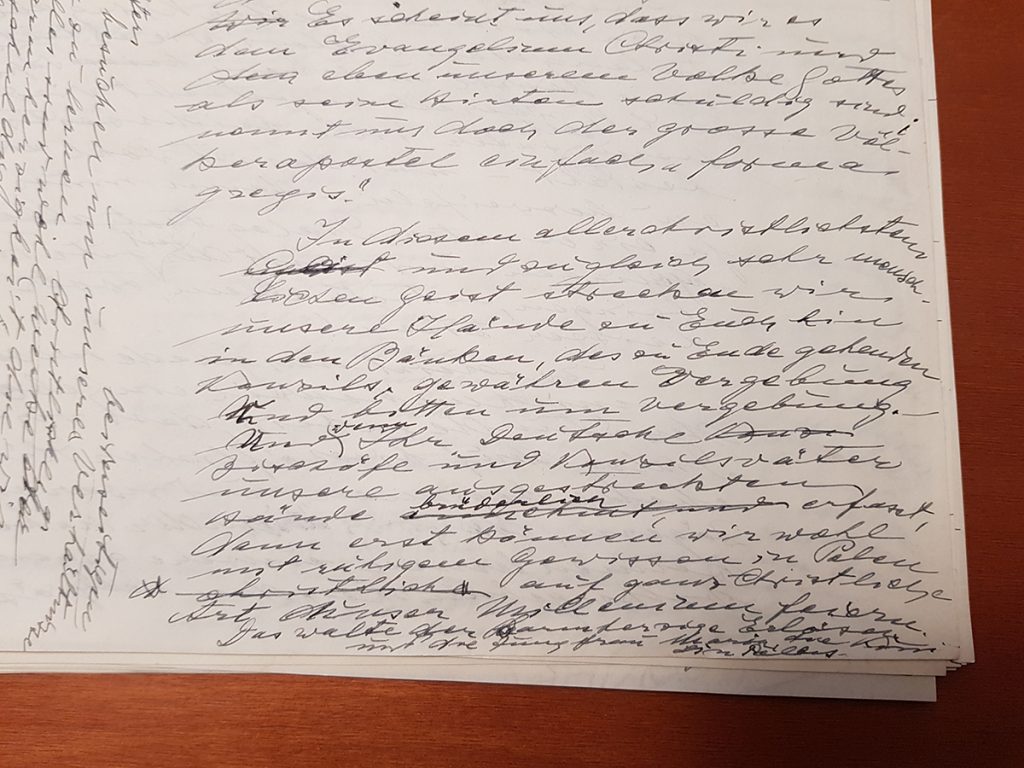

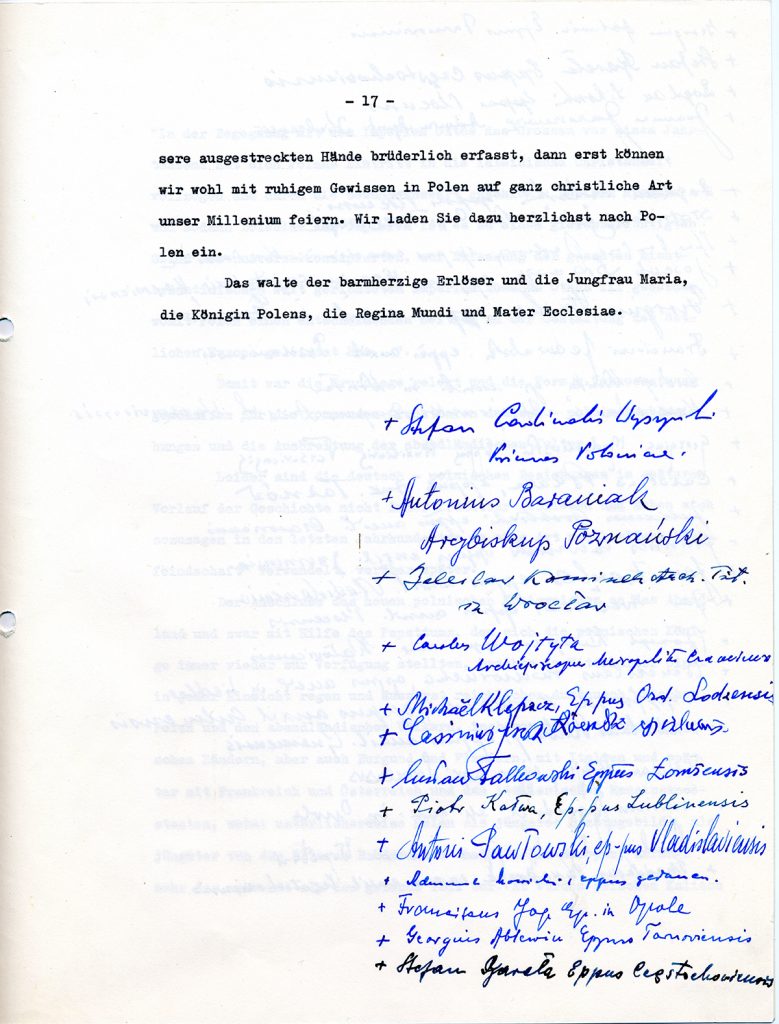

According to Father Zdzisław Seremak, secretary to Archbishop Bolesław Kominek in Rome, “The letter was written in Fiuggi, in a house run by the Elizabethan Sisters. It was created in an atmosphere of ardent prayer and solitude. The preserved manuscript was written at once in German as a continuous text: it covers 20 A4 pages. Then, the author himself applied the first correction and this version was typed. Already in the first version there is a famous fragment with the sentence “We forgive and we ask forgiveness” — “In diesem allerchristlichsten und zugleich sehr menschlichen Geist strecken wir unsere Hände zu Euch hin in den Bänken des zu Ende gehenden Konzils, gewähren Vergebung und bitten um Vergebung [emphasis by WK]. Und wenn Ihr Deutsche Bischöfe und Konzilsväter, unsere ausgestreckten Hände brüderlich erfasst, dann erst können wir wohl mit ruhigem Gewissen in Polen auf ganz christliche Art unser Millennium feiern” (“In this most Christian, but also very human spirit, we extend our hands to you, sitting here on the benches of the concluding Council, and we forgive and ask for forgiveness. And if you, the German bishops and Council Fathers, take our outstretched hands fraternally, only then will we, with a clear conscience, be able to celebrate our Millennium in a Christian manner”).

Even though several dozen different letters were sent, only this one made history. As early as in October, Bolesław Kominek wrote to the German bishops that this letter was of exceptional importance: “We attach much more importance to this Letter than to letters addressed to other episcopates. The intention is a rapprochement on the Christian plane. Please do not reject this mutual opportunity.”

When analysing the content of the Letter, elements of a historical lecture and a treatise of ethics can be seen in the document. In describing Polish-German relations, Bolesław Kominek broke with the model of official journalism and partly of historiography, according to which Polish-German relations were presented as always hostile and by definition hostile. He proposed a look at ten centuries of living as neighbours without stereotypes and taking into account the ideas of both sides, as well as with reference to both Polish and German historiography. Therefore, apart from problematic and difficult issues, such as the activity of the Teutonic Order in Poland, the participation of the Kingdom of Prussia in the partitions of Poland and, finally, German crimes during World War II, many positive aspects are described in the relations of both countries and nations, including colonisation under German law and the activities of religious orders, saints and artists of German origin in Poland. Breaking the taboos in force in Poland, the author of the text raised issues important for the German addressees related to the activities of the anti-Nazi opposition in Germany and the post-war displacement of the German population from the territories granted to Poland in Yalta and Potsdam. The main political problem in post-war Polish-German relations was also not overlooked, that is the border along the Oder and Neisse rivers, which was described as being “for the Germans an extremely bitter fruit of the last war,” and referring to German media — as a “hot potato.” The letter also included a request to the German bishops to thank the Evangelical community in Germany for their commitment to “finding a solution to our difficulties.” This was a reference to the so-called Eastern EKD Memorandum of 1 October 1965, in which German Evangelicals appealed to society and the government in Germany to engage in dialogue with Poland, accept responsibility for the consequences of World War II and recognize the Polish-German border. On an ethical level, Bolesław Kominek proposed to the addressees a model of dialogue based on truth, openness to conversation (without polemics), willingness to get to know each other and finally, in reference to the achievements of the Council and the program of the Great Novena, readiness to acknowledge faults and forgive the guilty.

In a political sense, this document was also an unusual and somewhat prophetic message. Referring to the concept of dialogue resulting from the teaching of the Council and referring to the pope’s activity in the international arena, Polish bishops anticipated actions that in the international area are referred to as détente. It seems that the Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish bishops to their German brothers in Christ’s pastoral office can be classified as a faith-based diplomacy undertaking. Through the field of activity created by the universal Church, the bishops could carry out tasks in the field of international relations, and base their conflict resolution strategy on peace and reconciliation, and thanks to contacts forged during the Council, they built lasting relations with the hierarchy of the Church in Germany. However, the communist authorities perceived the Letter as a threat. It was presented as an element of the American bridge building policy and an attempt to detach Poland from the Eastern Bloc. The bishops also really violated the foundations of Polish policy towards Germany. The Letter was addressed to the German episcopate, as if Germany were not divided, the problem of the western border was raised in it, as if the 1950 treaty signed in Zgorzelec did not matter, and finally a dialogue with a foreign entity had been begun, as if the authorities did not have a monopoly in this regard.

The Polish bishops, addressing the Germans with a message of forgiveness, entered the area of foreign policy and provoked sharp reactions on both sides of the Polish-German border.

To make political decisions, such as the 1970 agreement between the Polish People’s Republic and the Germany Federal Republic on the foundations of normalisation of their mutual relations, the 1990 Treaty on the Confirmation of the Existing Border and the 1991 Treaty between Poland and Germany on Good Neighbourhood and Friendly Cooperation possible, it required grassroots activities, a change in social attitudes, a change in stereotypes and a readiness to accept the other party.

The Address of the Polish bishops to the German bishops affected all these areas. As early as in 1967, most Germans expressed their approval of the Polish-German border. In 1968, in response to the Polish Address, a group of German Catholics issued an appeal to the German government for a full normalisation of relations with Poland (the so-called Bensberg Memorandum). Many researchers (e.g. Friedhelm Boll, Klaus Ziemer or Robert Żurek) point out that without the Address of the Polish bishops it would have been much more difficult to implement Willy Brandt’s German Eastern Policy. The Chancellor himself stated: “Exchanges of massages between the Churches and their members preceded any dialogue between politicians.” Egon Bahr even stated that “church initiatives prompted the chancellor to act more boldly than was advisable at the time.” The indirect effect of the Address was the visit of Chancellor Brandt to Poland in 1970, followed by the establishment of mutual Polish-German relations in 1972, and finally the extraordinary support of Catholic parishes and Protestant communities for Polish society during the period of martial law in Poland (1981-1983).

Wojciech Kucharski, PHD