Opening of the Second Vatican Council, 1962, OPiP

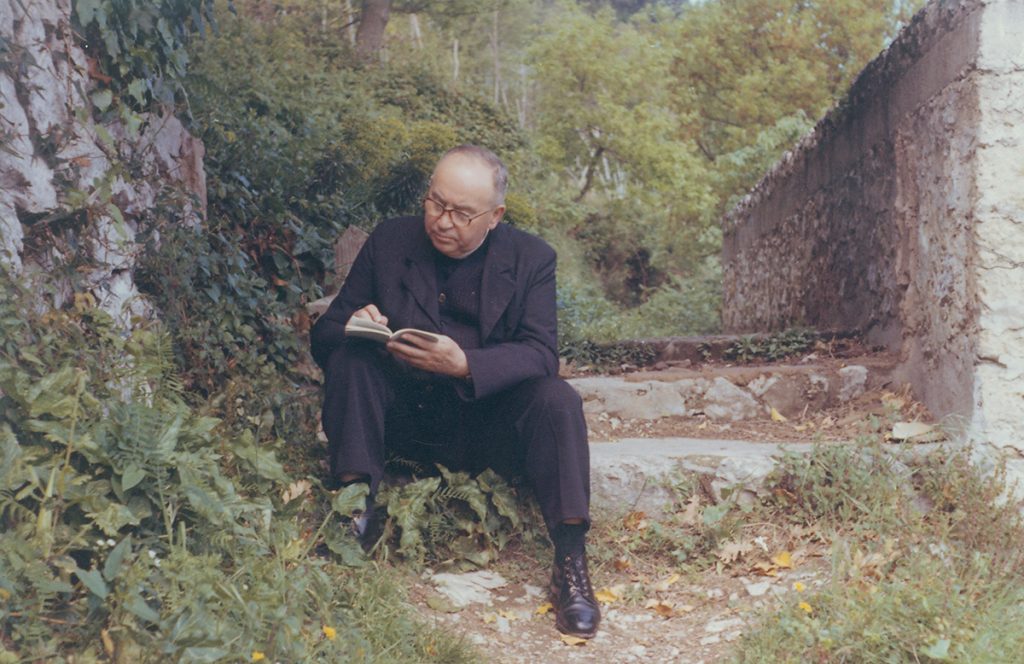

The Handwritten draft of the Address was written, on the initiative of the Primate of Poland cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, by the Polish Archbishop Bolesław Kominek originally in German between 8 and 13 October 1965, during the Second Vatican Council, in the convent of the Sisters of St Elizabeth in Fiuggi near Rome, Italy. Archbishop Bolesław Kominek was the most well-prepared person for this task due to the actions he had undertaken to improve Polish-German relations. He had written many texts on this subject, corresponded with many opinion-forming people, met with German bishops and activists, especially from the Pax Christi and Aktion Sühnezeichen circles, interested in improving relations with Poland (including Günter Särchen, Fr Kurt Reuter, Hansjakob Stehle). It should be noted that the author of the Letter in his earlier texts from the 1960s, in addition to defending Polish rights to the Western and Northern Territories, had called for dialogue and respect for German cultural heritage.

Archbishop Bolesław Kominek during a trip to Sicily, 1965; “Remembrance and Future” Centre

The Address – official typescript of the letter from Polish Bishops to their German counterparts, based on the handwritten draft, after final editing, was signed by Polish bishops on 18 November 1965 at the Polish Pontifical Church Institute in Rome. Then the document was delivered to the Rome seat of the Archbishop of Cologne (Germany), Cardinal Josef Frings, at the time president of the Plenary Conference of German Bishops.

The Address from the Polish bishops to their German counterparts contains a description summarizing Polish–German relations over a thousand years, but one contradicting the thesis of “eternal enmity”. The narrative indicates that in these accounts, apart from difficult, negative moments, such as the partitions of Poland in the 18th century and World War II, there were many periods of fruitful cooperation for both sides. It was also emphasized that through mutual influence Poland and Germany had contributed to the development of European civilization.

This document was also the first public act in which Poles mentioned the anti-Nazi opposition in Germany and the expulsions of Germans after World War II.

It should be noted that the Polish bishops took a great risk by writing to the Germans “we ask for forgiveness”. After all, it was only 20 years after the end of the war, and most Poles had in living memory the personal experience of German crimes on Polish lands. However, the bishops decided that it was not enough to forgive, but that one must also recognize one’s own faults.

The German bishops began to work on the Reply presumably on 25 November. According to the current state of research, the participants of this process were: Archbishop Alfred Bengsch of Berlin and Bishop Gerhard Schaffran of Görlitz as authors, Bishop Franz Hengsbach of Essen, eminent Church historian Hubert Jedin, and Rev. Bernhard Huhn Councillor of Görlitz as consultants, and the Rev. Wolfgang Große personal secretary to Bishop Hengsbach as secretary, with important imput of Cardinal Julius Döpfner. Archival material shows that the process of preparing the Reply to the Address was extremely intense and generated discussion among the German bishops, since the topic of reconciliation was considered very important and sensitive for Polish-German relations and the balance in the Cold War Europe. The text approved by the Plenary Conference of the German Bishops was translated into Polish presumably between 3 and 5 December 1965. The Reply to the Address was signed on 5 December 1965 in Rome and handed over to Polish Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński, Primate of Poland, Archbishop of Warsaw and Gniezno.

In the Reply, the German bishops admitted that Poles were suffering the consequences of the war caused by Germany, and in the post-war expulsions parallels were noted between Poles who had been displaced from the so-called eastern borderlands – Polish lands incorporated into the USSR, and Germans who had been displaced from the territories granted to Poland. The greatest importance, however, was to emphasize the possibility of close cooperation and friendship between the two nations.

It is also worth emphasizing that these documents recognize the efforts made by the German Evangelical community (EKD – Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland) for Polish–German understanding. Reconciliation was therefore treated as a task crossing confessional boundaries. The reference to the Evangelicals was part of the trend in Christianity known as ecumenism.

The bishops of both countries transgressed thinking in terms of the Cold War and the “Iron Curtain”. The best proof of this is that the Polish bishops sent a letter to all the German bishops, as if Germany were not divided into East and West Germany, and the bishops from West Germany and East Germany prepared a joint response on behalf of the entire German nation.

Referring to the concept of dialogue resulting from the teaching of the Second Vatican Council and referring to the activity of Pope Paul VI on the international arena, the authors of the Address and the Reply anticipated, to some extent, actions which in the international arena are referred to as détente. It seems that exchanging letters between the episcopates, apart from the spiritual and moral dimensions, can be classified as undertaking a faith-based diplomacy. Through the field of activity created by the universal Church, the bishops were able to carry out tasks in the field of international relations, they based the strategy of resolving the conflict on peace and reconciliation, and thanks to contacts forged during the Council, they built lasting bilateral relations.

Meeting between Cardinal Bolesław Kominek and Polish bishops, and members of the Bensberg Circle. From left to right: Karlheinz Koppe, Mechtild Fischer, Cardinal Bolesław Kominek, Elmar Maria Lorey, Rev. Prof. Norbert Greinacher, Manfred Seidler, unknown person;

Photo: Winfried Lipscher, “Remembrance and Future” Centre

The effects of the exchange of letters were quickly visible, first in terms of bilateral relations, and then in the European and global dimension. The first signs of changes in the mutual perception of both societies can be seen in a public opinion survey conducted in 1967 in Germany to examine the attitude of Germans displaced after World War II to the new Polish–German border. It turned out that, compared to 1966, the percentage of those accepting the new border had increased from 27 to 46%. In 1968, more than 100 intellectuals from the so-called Bensberg Circle (among whom was the then professor at the University of Tübingen, Rev. Joseph Ratzinger) appealed to the West German government to enter into political dialogue and recognize the final Polish-German border. The inspiration for this initiative was once again the exchange of letters between the episcopates in 1965. In 1970, the governments of the People’s Republic of Poland and West Germany signed an agreement concerning the foundations for the normalization of their mutual relations. Years later, Chancellor Willy Brandt said: “The dialogue between the churches and their faithful preceded the talks of politicians”. Indeed, Minister Egon Bahr, a close associate of the German Chancellor, even stated that “church initiatives prompted the Chancellor to act more courageously than was advisable at the time”. These bilateral relations bore fruit especially in the 1980s, when martial law was introduced in Poland. German society, especially Christian organizations, became involved in humanitarian aid for Poles, organizing the collection of food and necessities, which were distributed in Poland through a network of Catholic parishes.

Polish Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl gave each other a symbolic sign of peace emphasising not only good relations between the two countries, but also the closest partnership. NAF Dementi/“Remembrance and Future” Centre

Symbolic of the strengthening good Polish–German relations was the famous reconciliation mass in 1989 in Krzyżowa in Lower Silesia, Poland (where during World War II the Germans had organized an anti-Nazi opposition), attended by the Prime Minister of the first post–World War II non-communist Polish government, Tadeusz Mazowiecki, and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. In 1990, an agreement on the border was signed, and in 1991, an agreement on good neighbourliness. Germany became the main proponent of Poland’s accession to the European Union and supported Polish activities in the integration process.